Historical writing explores the past, connecting us to events and experiences that shape our present. It needs a sharp eye for detail and a strong commitment to finding the truth in past narratives. The historical essay is a key tool for scholars and students to engage with history, examine human actions, and add to our understanding of the past.

Writing a history essay is about transforming the echoes of the past into a captivating narrative. This process requires careful research, critical thinking, and effective storytelling. An essay should do more than just list facts; it needs to present a clear argument backed by evidence that supports the main idea. For example, when writing about the Civil War, it’s important to delve into the deeper causes and effects of the conflict rather than merely recounting battles. As we guide you through the steps of crafting a history essay, we invite you to enjoy the fulfilling journey of weaving historical details into a clear and thought-provoking story.

Understanding the Assignment

Starting a history essay begins with fully understanding the assignment. The prompts or questions given are essential and must be analyzed carefully. Break down the question, focusing on action words and what is being asked. Does the question want an analysis of causes, an evaluation of importance, or a comparison of events?

Your research scope serves as the foundation for your academic work. If it’s too broad, your history essay may only skim the surface of many topics; if it’s too narrow, you could overlook the rich context of significant events. Striking a balance is essential, allowing you to focus on a specific aspect of history that is both manageable and engaging. A clear understanding of your assignment involves defining the research boundaries, which will help shape the direction and depth of your essay. By the end of this process, you should have a solid grasp of your main question and a clear plan for how to explore your chosen topic. This thoughtful approach paves the way for an in-depth historical exploration that considers various dimensions of the subject.

Researching Historically

Research is the backbone of any history essay. This phase is where the seeds of your argument are sown and eventually nurtured into the robust plant of your final thesis. To build a solid foundation for your essay, it is essential to understand the types of sources you will encounter.

Sourcing Primary and Secondary Resources

Primary sources are the raw materials of history — original documents and objects which were created at the time under study. They are the unfiltered voices of the past, offering a direct window into past events. Diaries, speeches, letters, official records, and photographs are just a few examples. These primary sources offer direct insights into past events, providing a rich foundation for historical analysis.

Secondary sources, on the other hand, are one step removed from this immediacy. These are interpretations and analyses of historical events by later scholars. Books, journal articles, documentaries, and essays fall into this category. They provide context and scholarly debate that can enrich your understanding and support your argument.

Both primary and secondary sources are crucial. Primary sources offer the original narrative, while secondary sources provide the analysis that can help interpret those narratives. A well-argued historical essay deftly intertwines both, using secondary sources to frame and analyze the primary evidence.

Evaluating Sources

Not all sources are created equal. Evaluating sources for credibility, bias, and utility is a skill that can make or break your historical argument. In a research paper, this critical evaluation ensures that your sources are reliable and relevant.

Credibility is determined by the source’s origin — where, when, and by whom was it produced? Bias, while inherent in all sources to some extent, must be recognized and accounted for. Understanding the author’s perspective and how it might influence the information is crucial. Finally, utility asks how the source contributes to your argument. Does it provide the necessary evidence, or does it offer a critical interpretation that strengthens your thesis?

Note-Taking Strategies for Historical Research

Effective note-taking is essential for managing the information you gather. Begin by organizing your notes according to the type of source and how they connect to your essay’s main idea. Use a digital tool or a notebook to keep primary and secondary source notes separate, categorizing them by theme or argument. Don’t forget to include the citation details for each source.

Putting notes in your own words, except for direct quotes, helps you understand and start synthesizing the information. When you find important evidence or a strong interpretation, consider how it fits into your main argument. Reflect on how this evidence answers your central historical question and contributes to your thesis. Jot down your thoughts; these reflections can become the core points of your essay.

Researching history is like detective work. You need to sift through evidence, judge its reliability, and build a narrative. Your method of handling sources and taking notes will form the foundation for a strong argument based on the realities and interpretations of the past.

Crafting a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement in historical writing is the guiding star of your history essay. It presents your central argument and sets the stage for evidence and analysis. A strong thesis is specific, arguable, and significant. It should offer a clear perspective beyond a mere statement of fact, proposing an interpretation that can be challenged and debated. The significance of your thesis lies in its ability to shed new light on historical events, providing a fresh understanding or a novel perspective.

Examples of Effective Thesis Statements

- “The New Deal was a turning point in American political history, representing both the expansion of federal power and a transformation in the relationship between the government and the American people.”

- “Britain’s policy of salutary neglect before the French and Indian War contributed to the development of distinct American identities that would fuel colonial resistance to British rule during the American Revolution.”

- “The administrative and military strategies of the Roman Empire were crucial in maintaining its vast territories for centuries.”

Both examples present clear, debatable claims that set a direction for the essay and offer a lens through which the historical events will be examined.

Structuring Your Essay

structure of your essay is the skeleton upon which your narrative body will be built. Organizing the information in a clear and logical manner is crucial to guiding the reader through your historical argument. History essays benefit greatly from a well-structured approach that highlights key points and evidence.

Organizing Information Chronologically vs. Thematically

Chronological organization is straightforward, presenting events in the order they occurred. It is most effective when telling a story over time or detailing the progression of events. A thematic structure, however, groups information based on themes or particular aspects of the topic. This approach is beneficial when you need to compare and contrast elements or explore causes and effects across different times or events, such as examining industrialization in the nineteenth century versus the twentieth century.

Outlining: Building the Framework for Your Essay

Your outline should begin with an introduction that includes your thesis statement, followed by body paragraphs presenting a single point of evidence or analysis supporting your thesis.

- Introduction: Briefly present the topic, historical context, and your thesis.

- Body Paragraphs:

- Point 1: Present your first piece of evidence or argument directly supporting your thesis.

- Point 2: Offer additional evidence or a counterargument, further developing your thesis.

- Point 3: Continue to build your case with further analysis or evidence.

- Conclusion: Summarize your arguments, restate the significance of your thesis, and suggest implications or further areas for research.

Each point in the body of your outline should flow logically to the next, creating a coherent narrative that reinforces your thesis. Remember, the outline is not set in stone; it should evolve as your research and understanding deepen.

Writing the Draft

The first draft of your historical essay is your opportunity to transform your research into a captivating story. Remember, even seasoned writers stress the value of drafting and revising; it’s during this process that you can sharpen your arguments and enhance your presentation. Embrace this stage as a chance to bring your ideas to life!

The Opening: Setting the Historical Context

Your essay’s opening should establish the historical scene for the reader. Begin with a hook—an intriguing fact, a provocative question, or a brief anecdote—to pique interest. Follow this by setting the broader historical context that frames your thesis, providing the necessary background for the reader to understand the significance of the events or issues you are discussing.

Body Paragraphs: Developing Arguments and Analyzing Evidence

In the body paragraphs, develop your argument systematically. Each paragraph should open with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea or point of evidence. This helps in clearly linking your discussion to the broader historical events being analyzed.

The subsequent sentences should unpack this point, providing the relevant details and analysis. Use evidence judiciously—quote from primary sources to give voice to the historical actors and reference secondary sources to align with or counter scholarly interpretations. Make sure each piece of evidence directly supports your thesis and adds to the overall argument of your essay.

The Conclusion: Synthesizing Findings and Presenting Insights

conclusion is your opportunity to synthesize your findings and reinforce your thesis. Restate the central argument in light of the evidence discussed and underscore its significance. Offer insights into the implications of your findings and suggest avenues for further research, leaving the reader with a lasting impression of the depth and importance of your historical analysis.

Using Evidence Effectively

In history essays, evidence is your proof, your persuasion tool, and your means of engaging with the historiography. For instance, primary sources like speeches and letters are invaluable when writing about the Civil Rights Movement.

Integrating Quotations and Paraphrases

When incorporating evidence, balance quotations and paraphrases. Use quotations for impactful phrasing that you cannot rephrase without losing meaning. Paraphrase when you need to condense ideas and integrate them smoothly into your narrative. Both methods require proper attribution to their sources.

Citation Practices in Historical Writing

Citing your sources is essential; it shows your commitment to honesty and thorough research. Get to know the citation style that is commonly used in your field, such as Chicago or Turabian for history, and use it consistently throughout your work. Footnotes or endnotes should accompany any direct quotes, paraphrases, or references to specific ideas from other authors. These notes offer the necessary source information, enabling readers to follow your evidence back to its original context, which is crucial for the trustworthiness of your work.

Revision Strategies

Revising your first draft turns it into a refined essay. Most successful history essays go through several rounds of revision to ensure they are clear and cohesive.

In self-editing, assess the clarity of your argument, the relevance of your evidence, and the flow of your narrative. Cut superfluous content and strengthen weak arguments. Peer review offers fresh perspectives; your colleagues can pinpoint areas that need clarification and suggest improvements.

Finalizing Your Essay

In finalizing your history paper, meticulously proofread it to ensure clarity and coherence. Check that each sentence conveys its intended meaning and contributes to your overall argument. Confirm adherence to the relevant style guide, formatting footnotes, bibliography, and overall document layout according to academic standards.

History essays are more than academic exercises; they are vibrant engagements with the past, offering insights into our present and future. They challenge us to think critically, argue effectively, and understand the complexities of human history. Continue to explore, research, and write, contributing your voice to the historical conversation.

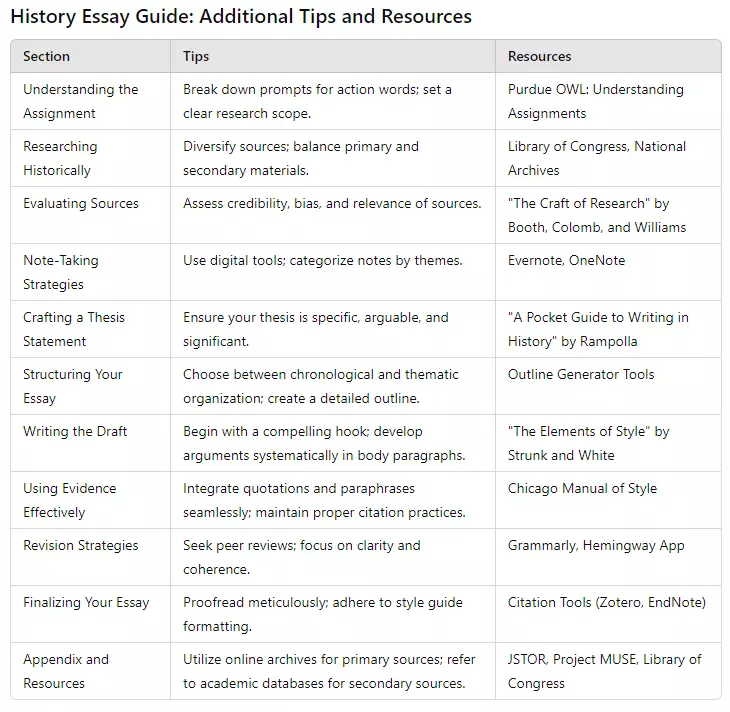

Appendix and Resources

For primary sources, explore online archives like the Library of Congress or the National Archives. JSTOR and Project MUSE provide a wealth of secondary literature. Improve your craft with works like “The Methods and Skills of History: A Practical Guide” by Conal Furay and Michael J. Salevouris and “A Pocket Guide to Writing in History” by Mary Lynn Rampolla.